Photo Gallery

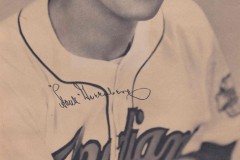

I’ve just completed a rather extensive update to the content on the site. It took me about 2 weeks to finish but I’ve scanned in the lion’s share of a prized photo album that was handed down to me from my Mother. I’m about to have a child myself and thought if I don’t get to it now I might never get to it. These images are of baseball, movies, articles, well wishes from fans and family. Click on the Photo Gallery drop-down pages above. I recommend using the “View with PicLens” option because it sizes the picture right for your screen. I hope you enjoy them!

Was Gene Bearden the only left-handed knuckleball pitcher to pitch in a World Series game?

Perhaps, depending on your definition of knuckleball.

Clarence Mitchell appeared twice (in 1920 for Brooklyn and in 1928 for St. Louis), in a long relief role in each case. Mitchell probably threw more of a knuckle-curve than what today is deemed a knuckleball, but it was called a knuckleball at the time.

Bearden, on the other hand, threw both a knuckleball (using the middle three fingertips of his pitching hand on top of the ball) and a spike curve (using the bent middle finger of his pitching hand on the ball). The Sporting News had illustrations of his grips in the issue that covered the World Series in 1948.

More recent left-handed knuckleball pitchers had some success in the major leagues–notably Mickey Haefner in the 1940s and Wilbur Wood in the 1960s and 1970s–but never made it to the playoffs.

Did you know he was in the movies?

An excerpt from the Stratton Story made in 1949.

He was also in The Kid From Cleveland also made in 1949.

As well as he has his own IMDB page. How cool is that!

Gene Bearden – The Unsinkable Man in Brown

by Ronnie Joyner

With long, afternoon shadows creeping across the Sportsman’s Park infield, number 30 walked off the mound for the last time as a St. Louis Browns starting pitcher. It’s quite possible that he had a sense of what the future held for his big league career as he flipped his glove onto the bench in the dugout and sat down, but you wouldn’t know it to look at him — he was a tough competitor. It was Sunday, September 21st, 1952, and fall was coming fast — and so was the Autumn of his big league career. He had pitched well enough to win that day, but like most of the Browns starters that season, he would take the loss. The White Sox’s young left-hander, Billy Pierce, was just a bit better — as were the Chicago bats — and it was Pierce who got the 4-1 victory.

Yes, he had pitched well enough to win on that September day, but like most of the games that he had pitched since he’d blazed his way into the record books with a 20-win rookie season just five years earlier, it was a struggle. But he was a fighter — he’d proven that in World War II and on ballfields all over America — and he was not about to let a struggle end his dream of pitching big league baseball.On March 18th, 2004 — over 51 years after his last start for the St. Louis Browns — Gene Bearden died of congestive heart failure in Alexander City, Alabama, at the age of 83. He and Lois, his wife of 59 years, had moved there in 2003 from their longtime home in West Helena, Arkansas, to be near their daughter, Gene Borowski. A son, Shea, died in 1996 from leukemia at age 51, but a grandson, Johnathan, survives.

Before he toiled for the Brownies as a fading star in 1952, Bearden streaked brightly through the baseball stratosphere as a 27-year old rookie with the Cleveland Indians in 1948. But, like a lot of players from that generation, it was a miracle that he should have ever played ball again — or even lived for that matter.

By the summer of 1943 Bearden was a machinist’s mate aboard the 10,000-ton cruiser, the USS Helena. The Helena had been one of the lucky ships to survive the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, but she didn’t come away unscathed. She was hit by a single torpedo in the attack, suffering damage that was not completely repaired until June of 1942. The Helena was very busy following her repairs, seeing action in the Guadalcanal campaign — but her luck was about to run out.

In the early morning of July 6th, 1943, the Helena was part of a task force that fought Japanese destroyers in the battle of Kula Gulf in the South Pacific. During the heavy combat, the Helena took three torpedoes and began sinking fast. In their well-drilled manner, all of the sailors went over the side. The men clustered around the bow of the ship as it rose in the air while sinking only to have the Japanese continue to fire upon them. 30 minutes after the Helena sank, two U.S. destroyers, the Nicholas and the Radford, were dispatched to rescue survivors. The rescue effort took a few days to complete because the U.S. destroyers were called back into combat whenever the enemy got too close. When it was all tallied, 168 of the Helena’s 900 men had perished.

One sailor who didn’t perish was Gene Bearden. He had drifted in a life raft with severe wounds to his head and knee before being picked up by one of the destroyers. He spent the next two years in a hospital where a metal plate was inserted in his skull and a metal hinge into his knee. Bearden came back to baseball with a vengeance in 1945, compiling a 15-5 record with the New York Yankees’ Eastern League club, Binghamton. He posted another fine season in 1946, winning 15 and losing only four for the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. It was in Oakland under manager Casey Stengel that Bearden developed the pitch that would his carry him to stardom — the knuckleball. He gripped it with the nails of his first three fingers and was able to deliver the ball to the catcher with virtually no spin, breaking sharply downward as it reached the batter.

On December 20th, 1946, the Yankees dealt Gene Bearden to the Cleveland Indians along with Hal Peck and Al Gettel in exchange for Sherm Lollar and Ray Mack. The Indians couldn’t resist taking a peek at their knuckle-balling phenom, so they kept him on the early-season roster in 1947 and sent him to the hill on May 10th in a relief appearance against the Browns at Sportsman’s Park. It wasn’t pretty. He pitched only 1/3 of an inning and gave up a couple of hits and three earned runs. That was his only big league appearance of ’47, which unfortunately never gave him an opportunity to lower the 81.00 ERA that will forever define his first year in the majors. Bearden had seen much worse shelling in the South Pacific than he saw on that day in St. Louis, though, so he was undeterred. Sent back to Oakland for more seasoning, he put together another great season for the Oaks going 16-7 with a 2.86 ERA. Despite his solid numbers down on the farm, Bearden was not guaranteed a spot on the Indians’ roster as they began spring training in 1948 — he would have to fight for it. He fought — and won — a spot on the Cleveland pitching staff, but he would have to wait nearly two weeks to get his first big league start.

The Indians were at Washington to play the Senators on June 8th, and Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau handed Bearden the ball. Bearden later admitted his nervousness about his first start, but he said that his roommate, third baseman Ken Keltner, gave him some valuable advice about pitching in cavernous Griffith Stadium.”Let them hit it,” Keltner told Bearden, “It’s a 10-minute cab ride to left field.” Armed with Keltner’s words of wisdom, Bearden went out and beat Washington’s Sid Hudson to gain his first major league win. That turned out to be the beginning of a true story book season for Bearden.

He won his next three starts before losing, 2-0, to the Nats at Municipal Stadium in Cleveland — Sid Hudson avenging his loss of three weeks earlier. Bearden was back in the win column in his next three starts to run his record to a heady 6-1. Then he encountered what could really be called his only slump of the season. He lost his next four starts in a row, but Boudreau stayed with the rookie and was rewarded when Bearden built his record to 15-9 by winning eight of his next 12 starts. And he was just getting started.

The Red Sox and Indians each had 87 wins before Bearden’s scheduled start against Washington on September 16th, and Boudreau decided that it was time to lean heavily on the hot hand of his rookie knuckleballer. He started five of the remaining 15 games on the Indians schedule, winning them all, often pitching complete games on short rest. His 8-0 shutout of the Detroit Tigers on October 2nd clinched at least a tie for the pennant with one game to play. A tie with Boston is exactly what they got, too, when they lost to the Tigers the next day to close out the 1948 regular season.

“At the moment,” Boudreau explained years later, “Bearden was my best pitcher — better than Bob Feller, better than Bob Lemon, better than Steve Gromek. He’d come through in the tough games for us all season, and I had absolute confidence in him.”

No longer the timid rookie that he was when he got his first big league start, Bearden also had absolute confidence. He later admitted that he was more nervous before his first start against the Senators in May than he was before the big playoff game.

Bearden’s performance in the playoff elevated what had been a nice Cinderella story through the course of the regular season to legend. He went the distance, frustrating the Boston batters with his herky-jerky delivery and allowing only five hits — and beat the Red Sox, 8-3, to win the American League pennant for Cleveland in what many consider the single most important victory in Indians franchise history. Ken Keltner helped his roomie’s cause with a decisive 3-run homer, but it was player-manager Lou Boudreau’s performance that day that really secured the deal. He led the Indians’ offensive assault with a 4-hit day — two singles and two home runs. Bearden was carried off the field on the shoulders of his teammates to a joyous all-night celebration.

The scene was funereal in the Red Sox club house. Boston manager Joe McCarthy had also bucked his regular rotation sending the aged Denny Galehouse to the mound to oppose Bearden, but unlike Boudreau’s gamble, McCarthy’s was a bust. Galehouse had been a hero in St. Louis back in 1944 when he helped pitch the Browns to the only pennant in their history, but he was running on fumes by the end of 1948. He took the loss in the playoff game — the last decision in his big league career.

As impossible as it seems, things only got better for Bearden in the World Series against the Boston Braves. With the series tied at one game apiece, Bearden started Game Three at Cleveland just four days after his playoff win. He was at his best in the game, shutting out the Braves on five hits for a 2-0 victory. Always a good hitting pitcher, he helped himself at the plate, too, slashing out a double and a single.

The Indians had a three games to two edge as they began Game Six on October 6th in Boston. Bob Lemon held a 4-1 lead in the game when he loaded the bases with one out in the eighth. Boudreau decided to go for the kill right then. Bearden was brought in to put out the fire on just two days rest. It appeared that Boudreau’s move might backfire when one run scored on a sacrifice fly and another crossed on a pinch-double by Phil Masi, but Bearden got out of it when Mike McCormick bounced a come-backer to him for the third out of the inning stranding the tying run 90 feet away.

Bearden went back out for the ninth and committed the cardinal sin of walking the leadoff man, but a double-play quickly erased the mistake. Then Tommy Holmes flied to left to end the game and the Series — and Bearden, just a week after being carried off the field for winning the pennant, was carried from the field again for saving the World Series. The Indians have not won another World Series since.

When asked about Bearden’s close scrape with blowing the lead in the eighth inning, Boudreau said he would have started Bearden in Game Seven the next day had the Indians lost Game Six. “It was Bearden’s Series,” he said.”That boy believes in himself,” teammate and future Hall of Famer Satchel Paige said following the victory, “And when you believe, you do.””Gene Bearden — give him credit,” said Red Sox second baseman Johnny Pesky. “He kept us off balance, and when he didn’t, we hit balls hard right at people.”

“He won the pennant and the World Series for us,” Bob Feller said shortly after Bearden’s passing last March. “If it hadn’t been for Gene Bearden, Cleveland would not have a world championship since 1920. He was a lot of fun, a good teammate.”

Bearden finished the 1948 season with a stellar record of 20-7 with a league-leading 2.43 ERA, six shutouts and 15 complete games. Even at the plate he could do no wrong as he finished the season with a .256 batting average and two home runs. Bearden rode the wave of his success right into the offseason. The 28-year old Bearden was a strong contender for the rookie-of-the-year award, but major league baseball only honored one player per year at that time, and the 1948 selection was National Leaguer Al Dark. The Cleveland baseball writers named Bearden man of the year. Lou Boudreau won the Hickok Award as America’s professional athlete of the year, but he insisted on humbly passing the trophy to his knuckleballing Series hero. Bearden even parlayed his on-field success and movie star good looks into a role playing himself in the Jimmy Stewart-June Allyson movie, The Stratton Story, that filmed in the offseason.

Bearden was at the pinnacle, but his career was a downward spiral from there. He was never again able to capture the magic that he had in 1948. He slipped to 8-8 in 1949 and saw his ERA balloon to 5.10. Some thought it could be attributed to arm trouble or a persistent thigh injury that had slowed him, but many insiders felt that Bearden’s downfall could be traced to one man — his former Oakland skipper, Casey Stengel. Stengel, who had taken over as manager of the Yankees prior to the 1949 season, supposedly informed his players of what he knew to be Bearden’s achilles’ heel — a fault previously undiscovered by his big league opponents. “His knuckleball dips out of the strike zone,” Stengel told his team.

“Casey told Yankee hitters that Bearden’s knuckleball broke so much that it was not in the strike zone when it crossed the plate,” a coach explained. “He told his hitters to lay off it. With three balls, Bearden then had to come in with a fastball, which they murdered. Word quickly spread around the league.”

Bearden never accepted the Stengel theory of his downfall, instead claiming that injuries lessened his effectiveness more than anything. Whatever the reason for Bearden’s trouble on the mound in 1949, it continued right into 1950. The confidence that Boudreau showed in Bearden in 1948 had completely dissipated by the summer of 1950, and with a record of 1-3 on August 20th, Cleveland put their hero on waivers.

Bearden was claimed by the Washington Senators, but they quickly found out that it was true — he no longer had the magic he possessed just two years earlier when he had picked up his first win at their expense. He struggled to a 3-5 record with the Nats through the rest of the 1950 campaign. The Senators gave him another look in 1951, albeit a short one. After just one appearance, Bearden was waived on April 26, 1951.

Now it was Detroit’s turn to take a chance on the fallen hero, and they claimed Bearden off the waiver wire. He continued to be plagued, though, by the same ineffectiveness that had dogged him in ’49 and ’50. In 37 games with the Tigers in 1951, Bearden pitched to a 3-4 record and a 4.64 ERA, and with numbers like that, he was dangerously close to being out of big league ball.

Only a bad team and a special owner would be willing to take on a reclamation project like Bearden. Enter the St. Louis Browns and Bill Veeck. Veeck was the Indians’ owner when they won the World Series in 1948, and he remembered well Bearden’s contribution to that team. Veeck put together a package trade with the Tigers on February 20th, 1952, and he made sure that Bearden was a part of the deal.

Despite his improved pitching in 1952, it was obvious that Bearden would never again be what he once was, and the Browns waived him on March 18th, 1953. The ’53 White Sox were the last big league club that Bearden would pitch for, and he was far from an embarrassment to them. Working almost exclusively out of the bullpen, Bearden compiled a 3-3 record with a tidy 2.93 ERA in 25 games. Still, he was not re-signed following the season, and at the age of 33, Gene Bearden’s major league days were behind him.Not yet ready to retire from the game he loved, Bearden pitched for four more years with minor league clubs in Seattle, San Francisco, Sacramento and Minneapolis. Life after baseball saw Bearden involved in a number of activities. He opened a few hamburger joints where his speciality was the large Bearden Burger, with sweet relish and a sesame seed bun, which came delivered by car hops on roller skates. He also owned an automobile dealership as well as working with a company that rented storage units.Bearden’s passing last March prompted his friends and teammates to recollect his big year. “Bearden won that big game for us,” said former Cleveland flychaser Allie Clark, 80, from his home in South Amboy, New Jersey. “There’s only a few of us left now.”

Former Indians outfielder Bob Kennedy, 83, is another surviving member of the 1948 champs. “Bearden was a baseball man,” he said recently from Chandler, Arizona. “He loved baseball. He was the big difference in ’48.”Johnny Pesky recalled a statement that Ted Williams made following the Red Sox’s crushing defeat in the ’48 playoff. In an eerie prediction, Williams said, “You watch, Bearden won’t win 20 games the rest of his career.” Teddy Ballgame was almost dead on as Bearden won only 25 more games after his rookie season.

Indians fans have never forgotten Bearden’s role in their last championship. In 2001, on the 100th anniversary of the Cleveland franchise, Bearden was chosen as one of the club’s 100 greatest players. “Indians fans will always remember his contributions to the team’s last World Series title in 1948,” current Indians owner Larry Dolan said in a statement following Bearden’s death in March. “His victory in the 1948 American League playoff game against Boston still ranks as one of the greatest wins in franchise history.”

New York Yankees Senior Advisor — and Number One Brownie Fan — Arthur Richman weighed in with his remembrances of Bearden from his office in Yankee Stadium. “In 1948 Gene Bearden was one of the best pitchers that ever played in the big leagues. He was never able to regain that edge, and I never really understood why. Still, I stuck by him until the day he died. Gene was a hell of a good guy.”

Despite Bearden’s fall from the heights of baseball stardom, he was never embittered at the sport he loved. After settling in West Helena, near his birthplace in Lexa, Arkansas, he devoted a lot of his time helping the local American Legion baseball team. Gene Bearden played a proud role in baseball history — and in our country’s history. St. Louis Browns fans should be proud to be forever linked to this true American hero.

Welcome to Genebearden.com

The intended purpose of this site is for Gene Bearden fans to come and learn more about the life and times of the man.